The First Servant’s stole, when it’s not on someone’s shoulders, hangs in the yuvrini in Qevellen. I’m standing in front of it, and even though I’ve seen it on Kor, and Kef, and Amath, I don’t want to touch it… now that I know about it. Which brings me to why I’ve sought it out. “The age of this piece is the only inconsistency I’ve found.”

Thirukedi’s voice is gentle. “Millennia do, in fact, consist of centuries. To say that the stole is centuries old is not inaccurate.”

“It’s not like Kor to soften the truth, though.” I turn to look at the shadowed figure standing at the back of the room. “Does he not know how old his own priesthood is?”

“I suspect he suspects,” Thirukedi says. “But I cannot say that he knows. As I do not remember myself, it would be unreasonable.”

That makes it make sense, then. If Kor had known a specific date, he would have been exact. But if he has only guesses, no matter how much he trusts them… about this, he would be vague. “It’s not centuries old, though. It’s thousands of years old. And it looks nearly new. You did something to it, didn’t you?”

Thirukedi draws up alongside. He’s several heads taller than me, and I’m not used to it; during our infrequent talks, we’re usually sitting, or in a room with elevated floors. It stresses His age, somehow… as if He’s talking down a great distance to reach me. I think of mountains, ageless and remote. “There are ways to preserve objects. The math proceeds from the Gate theory, and the error that produced me.”

“Do you keep many souvenirs?” I ask.

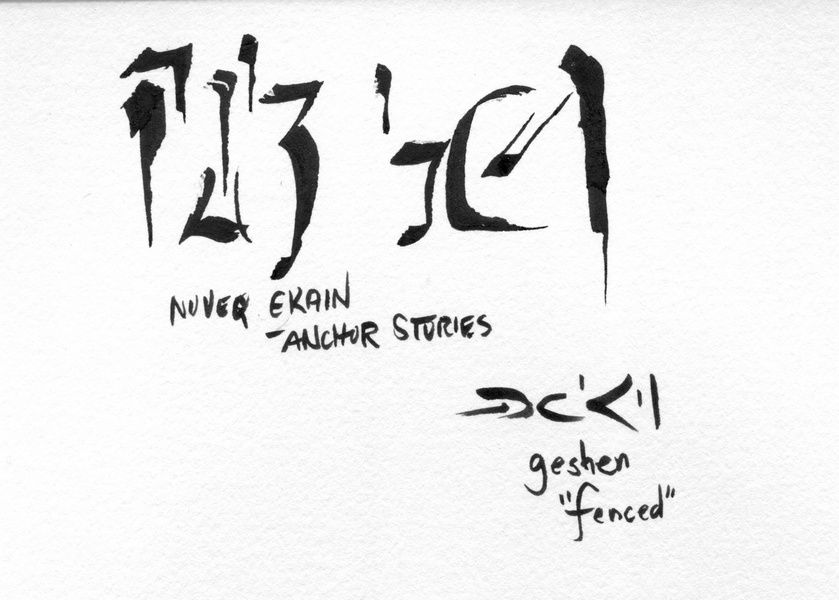

“Nuveq,” He says. “We call them anchors, when they are used to remind one of a memory, rather than a place… that is yavtil, souvenirs. One buys a yavtili with the intent to create a memory; one acquires nuveqi after they have become significant. Does that distinction make sense to you?”

“I think so,” I say.

He nods, a concession to aunerai body language. “To answer your question… no. I try to keep almost no anchors, datyani. But Tsevet came to me at a time when I was beginning to understand the ramifications of my condition. That I would lose even my nuveq ekain to time, and be contextless, and without memory.”

The pathos in this statement, even so calmly couched, is difficult to bear. That is probably why He littered it with linguistic puzzles certain to provoke tangential questions. It is a gift, and to reject gifts is uncouth. “Nuveq ekain… anchor stories.”

His smile is swift and shining. “You know this phenomenon. The stories that you tell and retell about your life. The ones you recall best, that define you.”

“The ones we end up telling our children,” I say. “Until they get tired of hearing them repeated and say ‘yes, you’ve already told me that story.’”

“When they are passed on that way in families, they are called novidil ekain,” He says. “Foundational stories. Because they form the foundations of the particular permutation of emethil that is your family.”

I like that, and it feels true to me: how the stories of the elderly become part of the toolset used by the younger generations to grapple with new experiences. That’s how it should work, anyway. I still hear in my head the stories told by my parents and grandparents, sometimes to hearing the exact cadence of sentences, word for word, in their voices. I return, now, to the important part. “You feared that you would lose your ability to remember these anchors to the stories that defined you, and so you would become… diffuse? Senile?”

“Geshen,” he says. “Is how we characterize the latter. Fenced in by increasingly narrow sets of memories and thoughts. But I feared nothing so specific. There were no precedents… how could I know? What it would be like? But Tsevet… Tsevet burned so brightly, datyani, that I thought I might not forget him. The possibility that I might was intolerable.”

“You preserved the stole, to fix that memory outside your own mind,” I said.

“I did, yes.”

“Do you regret it?”

His smile is sweet. “No. But making it imperishable was sobering. I did not want to lose my anchors… but I also did not want to clutter my life with them. And I had already decided that the stole should only be worn by one who could carry his legacy in full, and… as you know… I did not bestow it again for a very long time. Seeing it, unaging, as I myself did not age, was not a pleasant experience, and I was not motivated to make many more such anchors.” He reaches to the stole and trails elegant fingers down its edge. “Time passed, datyani, and my nuveq ekain eroded. I discovered then that Kherishdar itself was a greater anchor than any object I could save, and its story more foundational to who I am than any tale I might retell. I feared that I would lose my context and my soul with my memories… but my people told me those stories, and built that foundation around me, and I am whole.”

He goes, then, leaving me to the contemplation of the stole… and to the feeling that Kor was correct when he said that Thirukedi was no longer a man. I thought that was simply about his immortality; but I can’t wrap my head around the idea of not being designed by your memories… ‘fenced’, as they would say, into a shape you recognize because you are choosing it, year after year, with the ideas and memories that burn brightest in your mind.

When I look up again, it’s to Kef, standing near me, studying my face with the gravity he so rarely shows me. “Don’t look at it too long,” he says. “Some things aren’t wise to stare at, too long.”

“All right,” I say. And smile, a little “Thank you.”

He guides me out, and dims the lights, and we leave one of the Emperor’s few mementos behind.